Warning: The following post is loooooong and not for everyone. If you’re one of those millennials with the attention span of a jelly bean, apologies. Here’s a thing of a dog giving milk to a goat.

If you’re a B2B marketer selling technology and more than a little nerdy about how all this works, grab a cuppa.

–

There’s a naïve part of me that’s always kind of surprised to hear a company selling innovative products is struggling to find customers.

I call this part of me naïve because if there’s one thing this job has made me respect, it’s that selling (and even buying) innovative tech is incredibly hard.

In fact, the more innovative the product, the bigger the shift it signals. And the bigger the shift, the harder it is to swallow. Of course, none of this is news to anyone in the technology industry.

Still, the early-adopting homunculus in me can’t bear to see great new ideas get stifled by the cold and often ruthless nature of B2B tech adoption.

But ruthless it is.

And unless marketers appropriately organize themselves for the unique challenges of selling innovative technology, they run the risk of being as mystified as my inner homunculus when the people they’re selling to just don’t ‘get it’.

Now, everything you need to know about the challenges of selling innovation has been covered by folks like Geoffrey Moore and Clay Christensen.

But there is one specific type of situation that makes it even harder to sell innovative technology. And I haven’t really seen much said about it.

It’s when you’re selling both the disruptive technology challenging your category as well as the incumbent technology that currently defines it.

In other words, it’s when you’re both the hot new thing and the dancing dad.

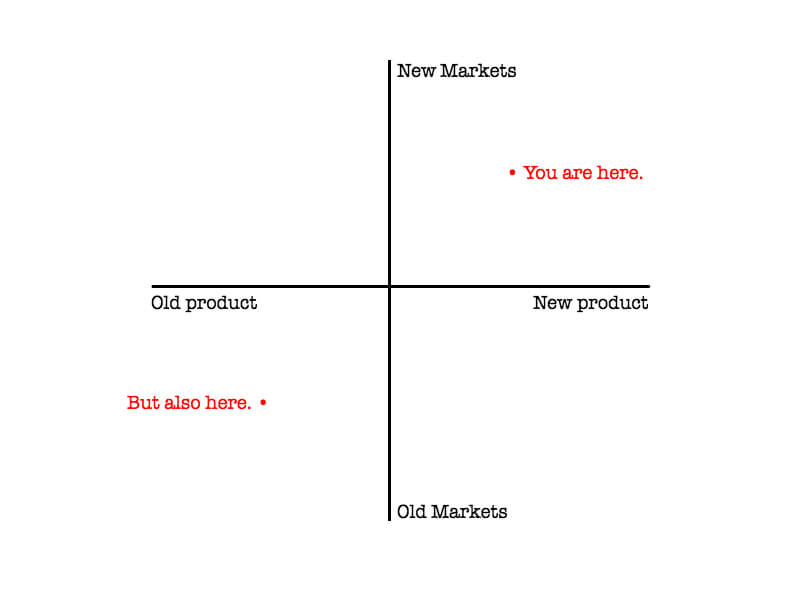

When you plot this on an Ansoff matrix (thanks Stan), you can start to see why this is all so hard. When you’re selling old products in an old market, all your focus is on increasing market share. But when you’re selling new products, you’re either looking for a new market or trying to establish one.

These are two completely different challenges.

The Ansoff matrix.

It’s a weird type of situation and admittedly not the most common one. But we’ve seen it enough to make me think it bears comment. And while it is fairly specific, I reckon it’s something more and more companies are going to have to deal with.

It’s worth noting that this situation isn’t quite the innovator’s dilemma*. Rather, it’s a situation that typically arises when successful companies bite the bullet and confront the innovator’s dilemma, committing to build the technology that might cannibalize their current cash cow.

It’s when your innovator’s dilemma progresses to turn into a marketing dilemma.

Why marketing an innovator’s dilemma is so hard

In many ways, this is exactly the kind of situation a technology company should want to find itself in. On one side, you’re capturing the money being spent on the old way of doing things. On the other, you’re capturing the money being spent on the new way of doing things.

What could go wrong?

- Your internal transition wont be easy

In practice, you have to think about the kind of product the company’s set up to sell. If you’re selling on-premise software, your salespeople are likely incentivized to bring in a small number of deals with huge up-front fees and implementation-heavy annual upgrades.

So if you start selling the cloud version of that software, they suddenly have to re-jig their processes and expectations to account for a greater volume of low monthly subscription fees. It’s a completely different model.

As marketers, it may be tempting to change the home page to make it all about the new cloud product, but if we aren’t careful we’ll end up hurting the core sales team who’ve made the company what it is today.

Even if the company does eventually transition towards an all- or most- cloud future, as marketers we have to help get that transition right.

How many leads for the old tech do we need for the next quarter in order to keep the old business ticking over? How many leads for the new tech can we even expect in the next few months?

- The buyers are totally different

The people buying the old way of doing things are not the same as the people buying the new way of doing things. You’re transitioning from people who were interested in a sure bet (laggards and/or pragmatists) to people who are interested in a risky but strategic leap forward (innovators and/or early adopters).

The technology adoption curve with Geoffrey Moore’s chasm included. Image credit

These aren’t just different groups of people, they’re fundamentally different kinds of people. The pragmatists are attracted to the fact that loads of other people buy and use your old tech. The early adopters are attracted to the fact that they might be one of the first people to adopt your new tech and take advantage of the strategic leap forward it enables.

This calls for different messages, different tactics and different benchmarks for success (getting a handful of the right early adopters vs. capturing most of the pragmatists).

Then there’s the question of the markets you’re selling into. If you’ve done your homework and re-read Crossing the Chasm, you’re likely going after a market where a small niche of early adopters are trying to use your tech to solve a specific problem.

Not only is this group likely smaller than the group you’re used to selling to, they’re likely in a completely different market too.

In selling new technology, we’ve seen companies go from selling to IT to selling directly to marketing; from selling commodity hardware to manufacturers to selling software to retailers; from selling old and boring tech to resellers to selling new and exciting tech-enabled services to the C-suite.

In theory there aren’t all that many differences between selling to CIOs and CMOs. People are people. But in practice, it’s a completely different job. And companies that CIOs know and value don’t become companies that CMOs know and value overnight.

These are big moves. And they necessitate the development of two separate marketing strategies.

- The category’s changing too.

Maybe your new tech is a smarter, better way of doing what your old tech did. Maybe your new tech empowers a new class of users to do what your old tech did. Maybe the chops you developed making your old tech are essential to deploying new tech and solving bigger problems with it.

Maybe all of the above.

In any of these cases, your company is pushing the boundaries of an existing category or discipline. And while that might be the kind of thing that sounds cool to investors, you can’t expect your existing customers to automatically love it.

In fact, the longer they’ve been proponents of the old tech or discipline, the harder it’s going to be for them to accept that a different way of doing things is obviously better.

As Robert Conquest notes in his three laws of politics, “everyone’s conservative about what they know best.”

This is an important point. Because as a marketer selling two divergent products, your instinct may well be to reconcile the differences and craft a unified message that cuts across both worlds.

In which case, you may well reach the conclusion that you should frame that message as the story of a category/discipline evolving.

But, as we’ve discussed, if you’re trying to convince a new market, they likely don’t care about the category you’re coming from. And if you’re talking about evolving the category/discipline, your old market might well resent it.

This is tricky stuff.

- You don’t get to do what every challenger needs to do

As if this wasn’t hard enough already, Der Kessler notes that you also have an additional handicap.

“The biggest bummer of marketing both the incumbent and the disruptor is that you can’t really do what an unencumbered upstart can (and must) do – attack the incumbent with all guns blazing.”

While you can and arguably should point out the limitations of the old way of doing things, you can’t do it nearly as clearly or emphatically as a start-up selling your disruptive tech would.

But you can’t show everything wrong with the old model. And you can’t ridicule its wastefulness.

“If, when it launched, Salesforce also had an on-premise version of their software, they couldn’t have laid siege to the on-prem model in the way that they did – a siege that fueled their amazing growth,” adds Doug.

No ‘no software’, no Salesforce. Image credit

As the incumbent, you’ve got handcuffs on. You’ll often need to be soft about things that are worth shouting. And if you’re competing against a bunch of young upstarts without the same ball and chain, you’re in for one hell of a ride.

Ok, so how the hell should I market my innovator’s dilemma?

So now that we’ve looked at why it’s so hard to sell both the hot new thing and the incumbent technology at the same time, I owe you some thoughts on what to do about it.

Well for starters, I think it’s important to address the fact that you are selling two different products. This may seem obvious. But marketers have to respond to people within the company who might be threatened by the new thing – as well as people within the company who want to threaten the old thing.

So it’s tempting to tell everyone we’re all one big, happy family and gloss over the differences between the two products or groups.

But you can only overcome these very serious (and not to be hyperbolic – threatening) issues if you admit this problem exists.

That being said, there are some more specific points worth considering. Obviously, there’s only so much I can say without diving into the specifics of any given case. So apologies for how general some of this might sound.

- Different audiences need different strategies

Bifurcating your marketing strategy can be hard. But when you’re selling to two different groups in two different markets with two different psychographic profiles in mind, you almost certainly have to.

This might well mean doing twice as much work too. So make sure you don’t stretch your people too thin when they have to start marketing on two different fronts. I’m going to stop short of personnel and resourcing advice because, frankly, that’s none of my beeswax.

But I will just say this – the most difficult decisions you’ll make here will be about prioritization. Say you need four pieces of content to tackle both segments. When it comes to producing that content, you’ll probably need to pick which product gets pimped first – the new one or the old one.

The people selling the old stuff will naturally demand theirs first. But if you have no content to attract prospects for your new product to, you should probably focus on filling those gaps first. I don’t want to be overly categorical about this – you’ll obviously know best.

But if there’s already demand for your old products, don’t be afraid to focus more explicitly on the new one.

- Consider separate brands.

If you feel like attacking the old model is definitely the way to go, then you might need to devise a new brand for your new tech.

For example, First Direct attacks traditional banking without hurting it’s parent company HSBC. GiffGaff can position itself as a different kind of mobile network because it doesn’t have to sound like Telefonica.

(It’s killing me that I can’t find a good B2B example of using separate brands to sell incumbent and disruptive tech. If you can think of any, please leave a comment. I’ve got a bad feeling I’m overlooking some really obvious cases.)

Given the costs of creating and maintaining a whole new brand, you might not want to go down that road. Just don’t be too quick to dismiss this route.

- If you’re evolving your category, don’t shy away from leading it too.

Remember that point about how the customers of your old product won’t automatically love your evolution story? That’s true. But it doesn’t mean you need to shy away from telling your customers what their future can and should look like.

“A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” – Steve Jobs

If building innovative products was safe, everyone would do it. So if you’re confident that your new way of doing things is the right way of doing things, be firm in your assertions and bold in your declarations.

This doesn’t mean you need to ignore the loyal customers who don’t want to make the move you’re recommending. On the contrary, you need to take their current position seriously and understand why it’s hard for them to change.

So in addition to content about your vision for the category or discipline, you might also want to do some content about what a transition from the old way to the new way should look like.

- It’s possible an evolution story isn’t strategically beneficial.

Alternatively, you might conclude that a story about the evolution of the category or discipline isn’t what either of your markets need.

Maybe your existing customers can continue to buy what they’ve always bought and achieve what they’ve always achieved.

Maybe your new prospects don’t give a crap about how your category’s evolving.

These are important considerations. You don’t want to default to an evolution story just because it encapsulates both your old and new tech and makes everyone in the company happy. This is about winning in two markets – not avoiding hurt feelings.

- You can sell both things. And they can buy both things.

It is entirely possible that the old technology will continue to be relevant to certain use cases.

When relational databases went up against non-relational databases, the initial noise was all about how NoSQL meant MySQL was dead. But it quickly became clear that both could, should and would co-exist.

This is true of cloud vs. on premise. Digital money vs. physical money. Mobile vs. PC.

Great B2B tech stories have a clear old way/new way structure. But you’re telling your story over multiple content pieces so don’t shy away from this kind of nuance – you can be a vendor selling both the old way and new way. And they can be a user of both the old and new way.

Clarify which use cases your old technology will continue to be relevant for so you can attract the right kinds of prospects for it.

- Manage expectations around your new tech.

I’ve alluded to this point a fair amount earlier in this post but it bears repeating – you can’t measure marketing success for the new tech in the same terms as you would for the old tech.

If it’s on-premise vs. cloud, you’re dealing with a different pricing structure and therefore different revenue implications. In on-premise you want the big up-front fees whereas in cloud you want loyalty.

While a confirmed sales call might be your end goal for on-premise tech, a sign-up for a free trial might be your end goal for the cloud tech. These are different indicators for marketing success and need to treated that way.

More broadly, you can’t expect a similar deal volume for your new tech as you would from your old tech. When it comes to selling new technology, you are necessarily trying to capture a niche – ideally, one that can eventually give you a foothold in other niches.

So manage your own expectations of what success might look like and then make sure everyone else knows they’re comparing apples to oranges.

–

Phew. Ok that was a whole lot of stuff you just read. So I’ll recap and conclude as quickly as possible.

Selling innovative tech is hard. But selling it when you’re also selling the incumbent tech is WAY harder.

Be very clear about what all of this means for your old customers and don’t skimp on learning about your new prospects.

Be confident in organizing yourself internally and framing your story for the market – and you’ll be able to traverse this minefield of issues.

The bad news is that this is going to be hard. The good news is that this is precisely the kind of situation every technology company should want to find itself in. And it’s precisely the kind of problem that calls for great technology marketing.

–

*I mention this because I’m sensitive to how specific Mr. Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation is intended to be.

Featured image credit: Incommensurable by Robert Couse-Baker

Enjoyed this article?

Take part in the discussion

Comments

There are no comments yet for this post. Why not be the first?