OK, bear with me. Something weird happened in 17th century English history. I mean, a lot of weird stuff happened – the gunpowder plot, the English Civil War, the Great Fire of London, gravity.

But something particularly weird happened in the way people communicated.

When the first English explorers* discovered** the east coast of North America, they confronted a strange New World filled with flora, fauna, geology and people they’d never seen before.

Naturally, they wanted to share their discoveries with people at home – for fame, fortune, conquest, escape, or otherwise.

But there was one small problem: not everyone believed them.

They’d seen something fundamentally new***, and convincing the Old World that their claims were credible – that the world existed as they said it did – was difficult for a few reasons:

- There was limited tangible proof (and photography wouldn’t arrive for another 200 years).

- The archetype of the pompous, exaggerating explorer was a popular trope in works of satire as early as 1605 (Captain Seagull in Eastward Ho! claimed Virginian settlers used gold chamber pots).

- The travel literature genre was gaining a reputation for being exotic, tantalizing and often totally fabricated (Walter Raleigh exaggerated so much in his 1596 The Discovery of Guiana he was eventually executed for treason)

Can you see where this is going?

They were going through all the pain of technology marketing. Long before those words even meant anything.

Then, as now, making big claims in a busy space to a skeptical audience – all with a questionable reputation – was tough as hell.

Marketing might actually be tougher.

We’re not just telling a (mostly illiterate) Joe Public that there’s a new bit on the map. We’re trying to convince someone who is explicitly paid for their expertise that we can make them better at their job.

So no, you’re probably not going to get scurvy at your hot desk, but equally Walter Raleigh never had to justify his digital transformation credentials.

Ultimately, I think we’re in the same boat. We’re all trying to convince people we’re the real deal.

And that’s where rhetoric comes in – for both of us.

Classical rhetoric and modern marketing

In lieu of any direct evidence, all those early explorers had was their word – literally.

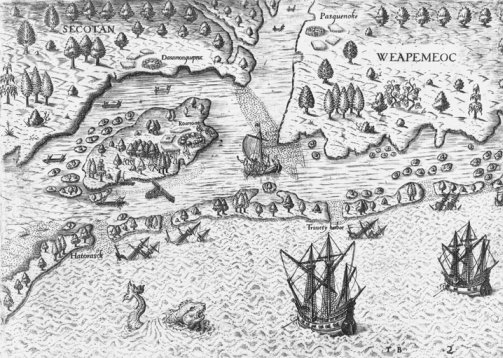

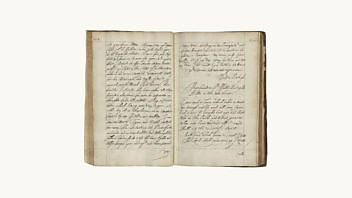

Diary entries, ship’s logs, topographical sketches, scientific reports and eye-witness accounts propelled the first generation of British settlers across an ocean and into the unknown (back when you had to do more than click to Discover more).

-

Virginia according to John White, 1585

Without any data or proof, explorers only had the classical rhetorical forms they learned at school to turn anecdotes and observations into structured, logical evidence that won over an audience of skeptics.****

And what’s really interesting is that when you dig into those documents, they’re filled with the same kinds of rhetorical framing devices we use today. Stuff like:

- Aggrandising your own value (or ab nostra persona)

- Belittling your opponent’s worth (or ab adversariorum)

- Flattering your audience (or ab persona auditorium)

- Appealing to the intrinsic value of your cause (or ab re ipsa)

That’s why you get titles scrambling to justify themselves, like:

And it’s why Richard Hakluyt’s 1584 Discourse of Western Planting ends with a Buzzfeed-esque conveyor belt of twenty-three reasons “to induce her Majesty and the state to take in hand the western voyage and the planting there”, including points like:

- The soil is good

- The journey there and back is “neither too long nor too short”

- It’d grow the Navy

- It’d increase trade (and generate masses of import tax)

- It’d piss off the King of Spain

And my personal favorite:

- England could offload “the children of wandering beggars…that grow up idly and hurtful and burdenous to this Realm” so that they might be “better bred up”

Early Modern welfare policies aside, Hakluyt zeroed in on his audience’s desires and anxieties like a laser.

It’s well-executed rhetoric – the intersection of relevant content and compelling delivery that bypasses skepticism and makes audiences lean forward.

And that’s just as powerful today as it was 400 years ago. Whether it’s driving transatlantic transplantation, or leads down a funnel, rhetoric can shape bold, outlandish – even unbelievable – claims into a compelling message that feels authentic, authoritative and persuasive.

(Of course, get rhetoric wrong and the costs haven’t changed either – you’ll still sound like a loudmouth charlatan pulling a scam.)

Importantly, while the function of rhetoric today is largely the same, its forms have evolved in some key ways.

So while there are still ways of speaking that build credibility and authenticity (or backfire and signal ‘superficial marketer at work’), they’re hard to pin down as precise concepts, much less “tips and tricks”.

To put it another way, Aristotle wouldn’t recognize much in the examples we’re about to explore.

Instead, we’re going to interrogate some common tropes and phrases through a rhetorical lens – to dig into the invisible heavy lifting they do and think about what we mean when we use them.

Because though the form of rhetoric has changed, the underlying goal is the same – to signal sincerity, authority and the solidity of the argument. It’s just that marketers today have to take a different route towards it.

Getting rhetoric right

Brian Vickers called rhetoric “the systemisation of natural eloquence”.

The challenge for marketers today is understanding what “natural eloquence” sounds like in context with the desires, anxieties and prejudices of their audiences. And that’s harder than it seems.

It’s not just that appealing to the authority of your God, your country and the divine right of Kings isn’t a great look for, say, supply chain software.

It’s that B2B buyers are subject matter experts so inundated and overstimulated by lacklustre marketing that clumsy rhetoric can amplify the stuff you’re trying to avoid.

Overfamiliarity. Presumptuousness. Insincerity. Flippancy.

Conversely, when rhetoric succeeds – when marketing achieves a natural eloquence – you reach the holy grail: your marketing stops sounding like marketing.

It just sounds…right. Like common sense, delivered with force.

Authentic. Authoritative. Persuasive.

But here’s the kicker: the difference between success and failure can be razor thin. Take a look:

“Here’s the thing…”

I’m a sucker for a good “Here’s the thing...” I think I once said “Here’s the thing” four times within a single blog post. That’s way too many.

But here’s the thing.

Here’s the thing is most powerful when you’re about to crystalize your whole message into a single, simple statement. It focuses the reader on what you’ve just said and what you’re about to say. It’s informal and authoritative. It builds rapport, and makes it seem like you’re pulling back the curtain and letting them in on what’s really going on here.

And if you’re not doing that (i.e. if you’re just using it as an empty signpost) you’re wasting your best shot to drive home your central point. At best, it’s a missed opportunity. At worst, you sound like you’ve got nothing to say.

“That’s why…”

Every industry and organization on the planet is grappling with seismic change at a breakneck pace. There’s almost never one correct response to brand new challenges, opportunities or conditions.

That’s why saying “The world has changed. That’s why we do X.” is a bigger deal than most marketers realize.

Because connecting your value proposition to a critical change in the world is powerful – it implies a kind of inevitable causality that positions what you sell as a natural solution to your market’s challenges.

But that causality has to ring true – not just in that it sounds feasible, but in that it makes sense. Otherwise you’re just another opportunist. In other words, the “how” is just as important as the “why”.

So yes, “Retail customer expectations are higher than ever”, but what are you actually doing about it?

“That’s why we deliver amazing experiences” doesn’t solve the problem you’ve set.

“That’s why our recommendation engine puts a personal shopper in everyone’s browser” matches the gravity it sets up.

“It’s win-win: you get X, your customers get Y.”

This little summary is an efficient way to quickly restate the key benefits for the different audiences you’re addressing. And again, it connects you to your customer’s world – they benefit, and so do the people they care about most.

(Just be sure you understand that world before talking about it. Appealing to some imaginary benefit for end consumers that doesn’t ring true for your customers will have the reverse effect, and actually place more distance between you and them.)

But be careful. Positive sum propositions can trigger an ok-but-what’s-the-catch skepticism if the underlying math isn’t immediately self-evident. If there’s a trade-off (like cost or complexity) make it clear, and if there’s not, have proof.

“But X isn’t just about Y. it’s about Y-and-then-some”

This is a great way to quickly establish and leverage a little unearned credibility. You get to both acknowledge the old way of doing things while also demonstrating that you’re advancing them. It positions you as a disruptor while also contextualizing your new, differentiated approach in terms the audience recognizes and values.

Of course, that all hinges on whether your new approach adds the right kind of value for your customers. Telling an audience of CISOs that your authentication solution “isn’t just about security – it’s about agile security” might communicate that you value jumping on the latest buzzword bandwagon more than taking their concerns seriously.

“…that’s where we come in.”

So you’re trying to do a whole bunch of things. But that’s really hard because of all these specific obstacles. That’s where we come in, to help you do more things, feel less pain, and solve all your problems.

This is a great call-and-response to romance your audience’s ambitions, pain-points and worldview, before pivoting to what you really came here to do: talk about your products and solutions. It can build rapport and relevancy in record time.

But if your description of their lives, problems, hopes and dreams is inaccurate, or too narrow, you’re going to alienate your audience before you’ve even introduced yourself. They’ll either presume you’re talking to someone else, or worse, feel a fundamental disconnect from your brand. Either way, they’ll go elsewhere.

Rhetoric is actually about respect

Powerful, effective rhetoric isn’t about quick tricks and emotional sleights of hand.

It’s about attempting sincere connection. That’s why it’s so damaging when it’s clumsily applied – because the audience can see the cynical maneuvering, and it reinforces all their worst prejudices about marketing.

Instead, natural eloquence is really about respecting your audience – about taking the time to understand not just what they need but who they are.

The most effective travel literature from the 17th century – the stuff that secured more funding and support for further voyages – didn’t try to brute force its way past skepticism with exaggeration and volume. Instead, it engaged with skepticism sincerely, worked to understand it, and made a powerful case to address it.

And the same is true of the marketing that builds loyal audiences and wins conversions today. It treats its audience with respect, and earnestly engages with their desires, challenges and skepticism, rather than just shouting the loudest or pushing its own agenda.

And the great thing is that on a long enough timeline, that natural eloquence stops being conscious rhetoric, and just becomes the way you speak to your audience.

*Colonizers

**for themselves

***to them

****There’s firm evidence for this. 17th century explorers were well educated, well-connected and well-funded. And education at the time was synonymous with rhetoric. Students would’ve pored over classic Latin works and been drilled in forms of rhetorical public address from an early age.

More from the Let’s Steal From series

The Beatles – or should we say the B2Beatles…

Holiday movies – Yeah, those. Polarizing but lesson-packed.

The Simpsons – The most successful TV show of all time has lots to teach.

The NBA – It was just basketball, then it took over the world.

Iceland air – How emphasising experience can make the middle of nowhere the destination.

The New York Times – You could do worse than stealing from the very best.

The MarTech Supergraphic – You too can build your own content powerhouse. Maybe.

The Democratic Mid-Term campaigns – Whatever you think about her politics, Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez sure is doing marketing right.

Follow The Frog – Making people feel bad is not the only way to raise money for charity.

Paths of Flight – Soothing plane videos from GE Aviation.

The Greatest Infographic Ever – From 1869. See it and weep.

Epic Split – Jean-Claude van Damme teams up with Volvo Trucks and they both come out of it very well.

Great First Lines of Novels – Incisive content from the likes of Orwell, Salinger and Garcia Marquez.

Rand Fishkin and Moz’s Whiteboard Fridays – Only one of the most successful and longest-running B2B content franchises ever made.

Airbnb City Guides – Crowdsourcing your way to content greatness.

TED Talks – SO much to steal here…

Enjoyed this article?

Take part in the discussion

Comments

OLaneVob July 14th, 2025

Hi, the whole thing is going fine here and ofcourse every one is sharing data, that’s truly good, keep up writing.

https://kfek.org.ua/holovni-fejly-pry-roboti-z-klej-hermetykom-i-yak-y.html